Seppure immersi nella torrida svagatezza che produce l’estate, ci sembrava il momento giusto per pubblicare alcuni lavori del poeta e traduttore ucraino Volodymyr Bilyk.

Dopo l’uscita di Ghérasim Luca “Pas de pas pas/Nessun padre”, torniamo sul percorso accidentato della traduzione (TRANS – prove di traduzione), con un autore che è veramente ostico rendere in italiano, se non con l’aiuto di una fitta rete di note a piè di pagina che diano conto di tutti i riferimenti e di tutti i giochi e le aberrazioni fono-linguistiche disseminate in ogni testo. TRANS – prove di traduzione però non ha come obiettivo principale quello di essere esaustivo o definitivo, deve piuttosto essere considerato come un tentativo, un primo approccio alla traduzione di un autore perciò, nel caso di Bilyk, Ermanno Moretti (traduttore) propone una traduzione articolata in più direzioni – senza avvalersi dell’apparato di note -, dovendo affrontare tra l’ altro imponenti gravami di non-sense, spesso costitutivi della poesia di Bilyk.

In primo luogo, perché un ragazzo ucraino di 25 anni decide di scrivere in inglese piuttosto che nella propria lingua madre?

Direttamente da Volodymyr veniamo a sapere che la lingua con cui lui è cresciuto non è l’ucraino e nemmeno il russo. È un russo differente: il soviet. Una lingua e un linguaggio di oppressione, d’incertezza, paura, miseria, dolore e vergogna, odio e disparità. Nessuno spazio per il gioco, il divertimento. Nessuno spazio nemmeno per una poesia che ha in sé lo stigma della libertà e una necessità altissima di esprimerla. Lo stesso varrà più avanti anche per l’ucraino, non sarà sufficientemente flessibile, malleabile, per adattarsi alle necessità ritmiche e sintattiche dell’autore.

Ecco qui il cambio, legittimo – e legittimato come capiremo leggendo – nella lingua che più di ogni altra avvicina l’universalità. Certo i motivi non sono da attribuirsi a una ricerca di maggiore visibilità, ma probabilmente è grazie a questo cambio che noi, oggi, ne stiamo parlando.

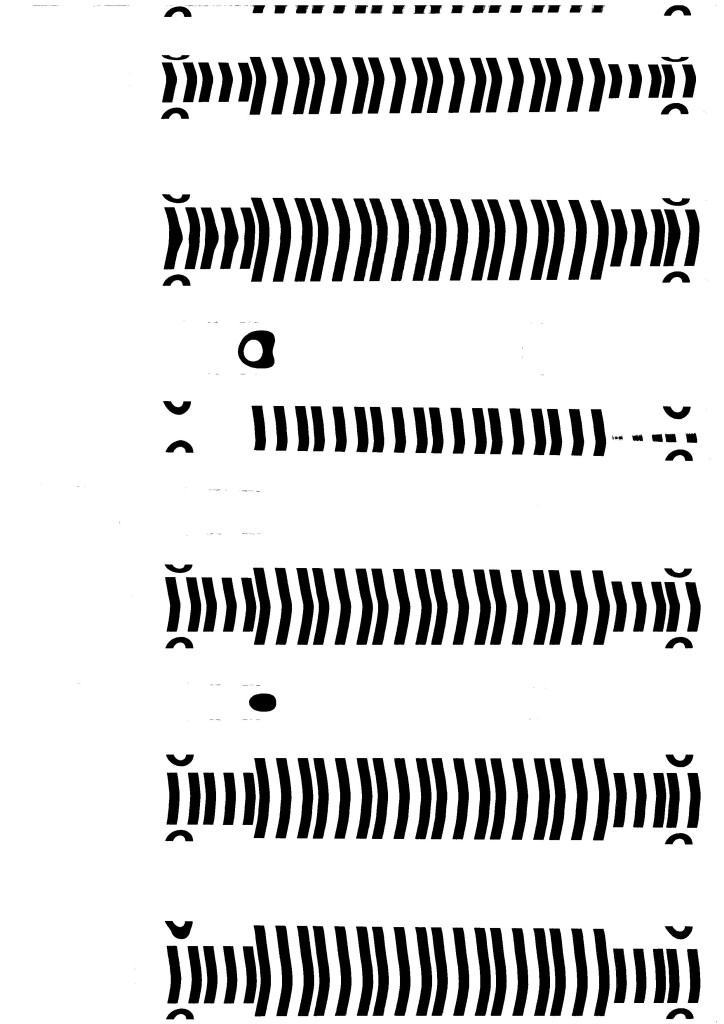

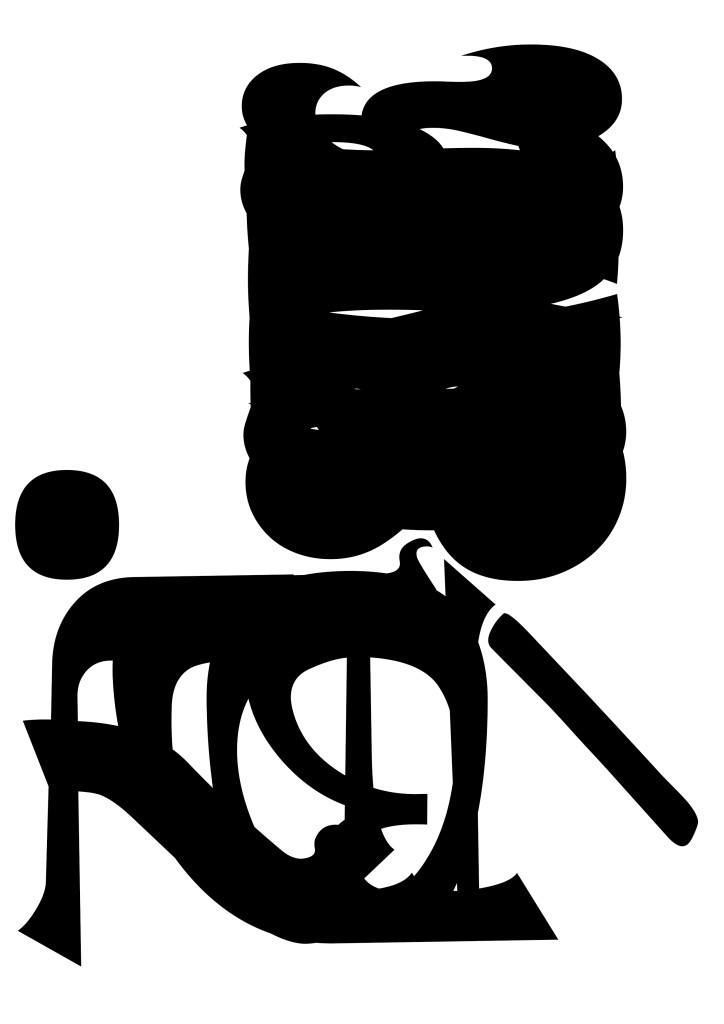

Il giovane Bilyk si occupa anche di poesia concreta e scrittura asemica, abbiamo inserito nell’ebook alcuni lavori e altri potete vederli direttamente qui nell’articolo, ma ci siamo maggiormente concentrati sulla sua produzione ‘lineare’ in quanto rappresenta bene uno degli aspetti di scrittura divergente e anche di complessità che f l o e m a si è prefissata di scoprire e di analizzare. Tutta la forza dirompente della scrittura di Volodymyr si può racchiudere in una sua battuta che potrebbe essere stata proferita da Groucho in persona: “Why should I write like somebody else especially when I’m not somebody else?”.

La poesia di Volodymyr è fresca, divertente, difficilmente etichettabile. Fatto proprio il pensiero di Wittgenstein e fedele al concetto poundiano del Make it new Bilyk si addentra nei labirinti del linguaggio con facilità assoluta. E per farlo si avvale di citazioni letterarie, musicali e cinematografiche, nonché di un’enorme dose di inventiva, grattando, anche in modo assurdo e paradossale i limiti evidenti del reale, per mostrarci quanto siano labili i confini dell’interpretazione e il distacco tra il linguaggio e ciò che esso rappresenta.

In questa antologia ci sono in particolare due poesie di stampo wittgensteiniano che possono essere considerate paradigmatiche del Bilyk-pensiero e sono SOMETHING e LONG BLACK LINE di cui riportiamo due estratti:

SOMETHING

Now, if you had to be? Ha? Do what? Do with what? Do with what is what was? Something out of something. Something is something. This it is, and it is this and that. Here, for some reason, something about something with something. Someone. Something. There. What is something that somehow is something. Something Something.

Something like a something something. Someone who has. Who is something. And who has. A certain something. A certain someone. Someone is something somehow. Someone and something is something something. And something something something something is something. Someone something something something. Someone is somehow something something. Someone is in something which each something in something something, something something.

something is something. something is something. something is a certain something. something is something that is something in something. something in something is something. something is something. something is a certain something. something is something something something. something is something in something which is something with someones something. then something is something with something. something is a certain something with something. something is a certain someone with something someone is certain. something is a certain something of someone certain of something. then something is somethings something. something is something. A certain...

[…]

LONG BLACK LINE

Black line is longer than the previous. Black line of length equal with the previous. Black line is longer than the previous. Black line shorter than the previous. Black line is longer than the previous but shorter than the line which is preceeding the shorter one whic suceeds the longer one. Black line of length equal with the preceeder of the previous line but longer because it starts earlier than the line which is the preceeder of the previous line to which this line is equal in length. Black line of length equal with the previous but it starts later than the previous line so it is shorter than the previous line. Black line is longer than the previous. Black line is shorther than the previous.

Black line is longer than the previous but it starts earlier than the previous so it is even longer than it seems to be looking at their tails.

[…]

In questi due componimenti Bilyk gioca con la logica proposizionale nel chiaro intento di mettere in crisi le normali capacità deduttive del lettore e forzando anche gli aspetti percettivi della pagina, grazie alla reiterazione variata delle stesse parole, che producono comunque significato. Se da un lato queste caratteristiche possono essere considerate come prolegomeni ai suoi lavori più segnici di poesia visuale e asemica, dall’altro Bilyk ci induce a riflettere che una parola è segno (long black line) ed è qualcosa (something), dunque un codice per quanto condiviso rimane sempre e prima di tutto un insieme di segni e perciò personalizzabile e strumentalizzabile, anche, a proprio piacimento. Nel caso della personalizzazione avremo nella migliore delle ipotesi un livello comunicativo alto, implicativo ma per deduzione, evocativo per logica trasversa, con tutte le difficoltà che una meccanica complessa può produrre. Nei casi di bassa e media entità avremo invece idiolettismi per lo più autoreferenziali.

Quando invece si parla di strumentalizzazione del codice, si va verso un’ambiguità prodotta dall’e(s)tica del profitto, dunque si perviene naturalmente al campo della ‘politica’, dove per ‘politica’ si intenda tutto ciò che afferisce a sistemi di potere. Lo sradicamento linguistico subito e cercato da Bilyk può essere considerato come una sorta di schizofrenia dell’identità linguistica che ha come risultato non tanto la creazione di una lingua nuova, quanto il pervertimento logico del codice logoro di partenza. Ciò avviene attraverso la liberazione dell’inconscio di stampo spesso surreale, con prelievi continui e quasi mai contigui dai più disparati serbatoi della cultura e del pop e con riaffioramenti dalle diverse lingue che creano un’ambiguità non di tipo strumentale, ma ironicamente rivoluzionaria. È inevitabile pensare a Bilyk come al fool che profferisce la cruda verità al suo re avvalendosi di un linguaggio in apparenza insensato, oscuro e altrettanto inevitabile (anche se Bilyk è ucraino) è lo scivolare del pensiero verso quelle isole Solovki teatro di uno dei primi e più terribili Gulag della Russia, dove artisti scrittori e cantautori riuscirono a creare un codice nuovo, una cifratura che desse almeno la sensazione della libertà, irridendo il potere che li stava uccidendo. (Ermanno Moretti & Daniele Poletti)

L’ebook “undestanding (of language) are not enough/la comprensione (del linguaggio) non basta” può essere consultato e scaricato anche in PDF su Biblioteca di f l o e m a o direttamente qui sotto attraverso la piattaforma ISSUU per la lettura di ebooks e documenti:

* * *

Although immersed in the hot chaos that summer brings, we thought this was the right moment for publishing some works by the Ukrainian poet and translator Volodymyr Bilyk. After the Ghérasim Luca “Pas de pas pas/Nessun padre” issue we’re back on the bumpy ride of translation (TRANS – prove di traduzione) with an author really hard to convey in Italian if not using an endless series of footnotes to give the reader all the references, all the games and all the phonolinguistic aberrations scattered in every poem. TRANS – prove di traduzione does not have as main objective being exhaustive or definitive, it must be regarded at as an attempt, a first approach to the translation of an author. Therefore for this ebook Ermanno Moretti (translator) offers a multi-directions translation – without using any footnotes – having to deal with imposing encumbrances of nonsense often constituting Bilyk poetry.

First of all, why does a 25 years old Ukrainian guy decide to write in English rather than in his mother tongue? From Volodymyr himself we know that the language he’s grown up with is not Ukrainian and not even Russian. It is a different Russian: Soviet Russian, oppressed, clinched and pathetic language of fear, uncertainty, misery, pain, shame, despair and hate. No room for fun. And no room either for a poetry which is a full expression of freedom. Later, even Ukrainian won’t be flexible and malleable enough, to adapt itself to the needs of rhythm and syntax of the author. And here’s the change, legitimate -and legitimized as we’ll understand reading- in the tongue that more than all the others approaches to the universality. Reasons are not no be found to a search of

greater visibility, but it’s probably thanks to this that, today, we’re talking about.

The young Bilyk deals even with visual poetry and asemic writing, we included some of these kind of works in the ebook and others in the short article you’re reading, but we mostly focused on his linear poems because it well represents the aspects of diverging writing and complexity in which f l o e m a is most interested for discovering and analyzing. All the Volodymyr’s explosive force could be summed up in one of his jokes that may have been proffered by Groucho himself: “Why should I write like somebody else especially when I’m not somebody else?”.

Volodymyr’s poetry is fresh, funny and hard to be labeled. Being an adept of Wittgeinstein ideas and faithful to Ezra Pound’s concept of ‘Make it new’ Bilyk delves into the labyrinths of language with absolute ease. And to do that he uses music, film and literary quotations and a lot of inventiveness, scratching, in a way that sometimes could be considered absurd and paradoxical, the obvious limitations of the real, to show us the evanescent interpretation borders and the gap between language and what it represents. In this anthology you’ll find a couple of poems that can be considered paradigmatic of Bilyk’s thought: SOMETHING and LONG BLACK LINE of which we give two extractions:

SOMETHING

Now, if you had to be? Ha? Do what? Do with what? Do with what is what was? Something out of something. Something is something. This it is, and it is this and that. Here, for some reason, something about something with something. Someone. Something. There. What is something that somehow is something. Something Something.

Something like a something something. Someone who has. Who is something. And who has. A certain something. A certain someone. Someone is something somehow. Someone and something is something something. And something something something something is something. Someone something something something. Someone is somehow something something. Someone is in something which each something in something something, something something.

something is something. something is something. something is a certain something. something is something that is something in something. something in something is something. something is something. something is a certain something. something is something something something. something is something in something which is something with someones something. then something is something with something. something is a certain something with something. something is a certain someone with something someone is certain. something is a certain something of someone certain of something. then something is somethings something. something is something. A certain...

[…]

LONG BLACK LINE

Black line is longer than the previous. Black line of length equal with the previous. Black line is longer than the previous. Black line shorter than the previous. Black line is longer than the previous but shorter than the line which is preceeding the shorter one whic suceeds the longer one. Black line of length equal with the preceeder of the previous line but longer because it starts earlier than the line which is the preceeder of the previous line to which this line is equal in length. Black line of length equal with the previous but it starts later than the previous line so it is shorter than the previous line. Black line is longer than the previous. Black line is shorther than the previous.

Black line is longer than the previous but it starts earlier than the previous so it is even longer than it seems to be looking at their tails.

[…]

In these two poems Bilyk plays with propositional logic in the clear intent to undermine the normal detective skills of the reader and forcing even the perceptive aspects of the page, thanks to the varied repetition of words which still produce meaning in any case. While these features can be considered as prolegomena to his works of visual and asemic poetry, on the other hand Bilyk induces us to think that a word is a sign (long black line) and it is something (something), like a code although commonly shared remains first and foremost a set of signs and so customizable and exploitable, also, to your liking. In case of customization we may have a high level of communication, implicative but by inference, evocative for transverse logic, with all the difficulties that a complex mechanism can produce. In cases of low and medium

entities we would have instead mostly self-referential idiolectism. But when it comes to manipulation of the code, it is moving towards an ambiguity produced from both ethic and esthetics of profit, therefore, naturally comes to the field of ‘policy’, where by ‘policy’ is meant everything that pertains to systems power. The linguistic uprooting suffered and sought by Bilyk can be considered as a kind of linguistic identity schizophrenia which has as results not really the creation of a new language, but more likely the logical perversion of the starting worn-code. This occurs through the release of the unconscious often surreal mold, with continuous sampling- and almost never contiguous from many different tanks of culture and pop and with resurfaces from different languages that create an ambiguity not instrumental, but ironically revolutionary. It is inevitable to think Bilyk as the fool who utters the harsh truth to his king making use of a language foolish in appearance, dark and equally inevitable (although Bilyk is Ukrainian) is the slip of thought toward those Solovki islands scene of one of the earliest and most terrible Russian Gulag, where writers, artists and songwriters were able to create a new code, a cipher that would give at least the feeling of freedom, mocking the power that was killing them.

Un ringraziamento particolare a Stefano Pocci e Jane Erkkila per il supporto e la revisione alla traduzione.

Volodymyr Bilyk is a writer, translator from Ukraine.

His works include: visual poems in the series This is Visual Poetry (2013), CIMESA (2013), Casio’s Pay-Off Peyote (2013), SCOBES (2013), THINGS (2014), Laugh Poems (2014), Vispo Ay Ai Ay (2014), “To When Tea Ties Hence to Wank It Too” / “Eminent Means of Basil Dado Hem-Welt” in The Chapbook 5(2015), “Heartbeat, Footclick, Machine Gun Vocalizes” (2016), Roadrage (2016) and screenplays for the films “Midget-Stripper” (2012-2013), “The Trial of Beilis”(2013-2015), “Escapee” (2014), “Joan the Battalioner” (2014), “Waking” (2015), “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” (2015-2016). His works were exhibited on Bright Stupid Confetti Asemic Show, Yoko Ono Fan Club, Venti Leggeri in Bologna, The Spiral Asemic Show in Malta; EL MARTELL SENSE MESTRE in Barcelona, The Future is Here Again: VISUAL LANGUAGE in New York, 1st International Literary Fair of Mato Grosso (2015), World Association of Visual and Experimental Artists in Valjevo and OVERCONSUMPTION in Ternopil. He is contributing editor of Utsanga.it.

His works include: visual poems in the series This is Visual Poetry (2013), CIMESA (2013), Casio’s Pay-Off Peyote (2013), SCOBES (2013), THINGS (2014), Laugh Poems (2014), Vispo Ay Ai Ay (2014), “To When Tea Ties Hence to Wank It Too” / “Eminent Means of Basil Dado Hem-Welt” in The Chapbook 5(2015), “Heartbeat, Footclick, Machine Gun Vocalizes” (2016), Roadrage (2016) and screenplays for the films “Midget-Stripper” (2012-2013), “The Trial of Beilis”(2013-2015), “Escapee” (2014), “Joan the Battalioner” (2014), “Waking” (2015), “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” (2015-2016). His works were exhibited on Bright Stupid Confetti Asemic Show, Yoko Ono Fan Club, Venti Leggeri in Bologna, The Spiral Asemic Show in Malta; EL MARTELL SENSE MESTRE in Barcelona, The Future is Here Again: VISUAL LANGUAGE in New York, 1st International Literary Fair of Mato Grosso (2015), World Association of Visual and Experimental Artists in Valjevo and OVERCONSUMPTION in Ternopil. He is contributing editor of Utsanga.it.

http://cut-n-splash.tumblr.com/ (cut-up inifinite reverse comicbook)

https://www.facebook.com/something.in.the.nose/?ref=bookmarks (cut-up inifinite reverse comicbook)

Ermanno Moretti è nato a Pietrasanta (Lu) nel 1975. Vive a Viareggio. Da circa tre anni è diventato  membro della rivista di arti e letteratura [dia•foria per la quale sta curando attualmente alcune traduzioni dall’inglese di prossima uscita.

membro della rivista di arti e letteratura [dia•foria per la quale sta curando attualmente alcune traduzioni dall’inglese di prossima uscita.

Lascia un commento