We dedicate this post to composer Antonio Agostini, an artist close to [dia•foria: apart from appreciating his work, we are tied to him by a long time friendship and recently by a fruitful collaboration also.

[dia•foria worked throughout the whole 2012 for John Cage’s centennial: from the release of the special issue “1000 e una nota per John Cage”, to the celebrating event UnCage IT. Last, a brief panel during the Pisa Book Festival.

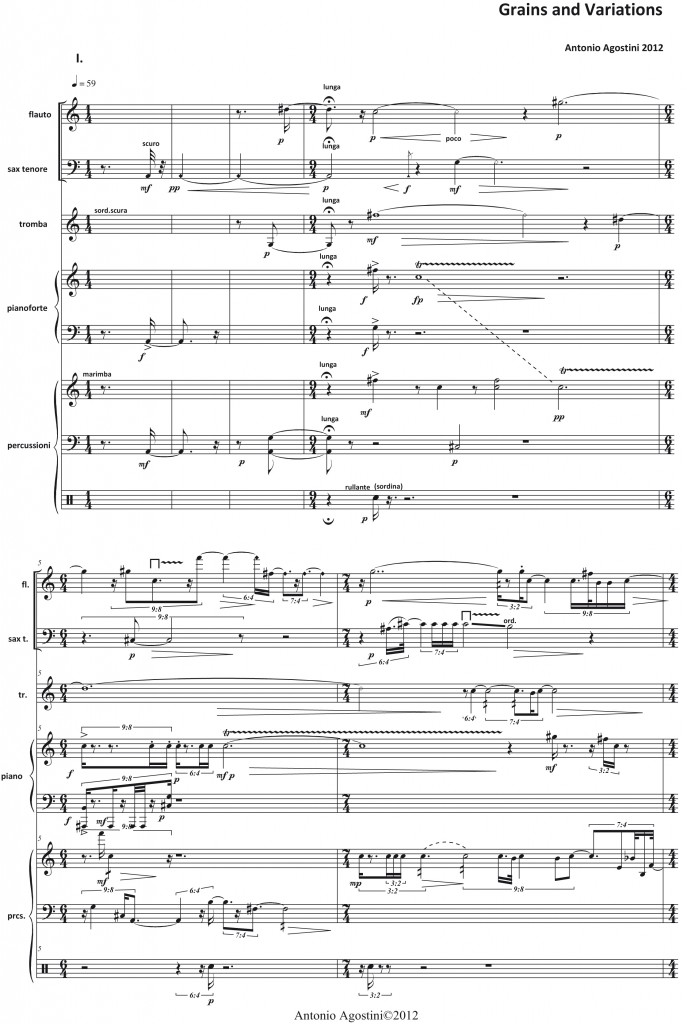

The UnCage IT event took place in Lucca, October 19, 2012, and Antonio Agostini’s piece was one of the highest and representative moments of the program. His work “Grains and Variations (for John Cage)”, was expressly written (we had commissioned it) for this event and was performed by the Cage Ensemble.

Here you can hear an excerpt:

[audio:https://www.diaforia.org/diaforiablog/files/2013/01/Grains-and-Variations-for-John-Cage-A.-Agostini.mp3]

1) Grains and variations is an original composition dedicated to John Cage and expressly written for his centennial; why a piece for John Cage and what impact he had on your music and education?

I come from a typical rock background, completely self-taught – I’m speaking about the beginning of the 80’s – so I began to listen to Cage by chance, because I read an interview with him in an Italian magazine (perhaps it was Fare Musica, I don’t recall the exact name), that focused on an happening in Rome. I was intrigued by the character and I started to search for both his albums and those of the so called American school. During my first years in the Conservatorio (school of music), I approached the Cagean experience of aleatoric composition and the usage of chance. However, it was just a juvenile episode, as I would never use those random processes in my compositions afterwards. Last year, on the occasion of his 100th birthday, I was given the possibility to pay homage to him for a celebrating concert in Lucca; it was a very interesting undertaking, since it opened ‘old drawers’ apropos of Cage, that I had closed some years before.

2) In your opinion, does it make sense to pay homage to Cage through a piece for him? Does it make sense to write such a piece if it is performed according to the musical practices that Cage tried to modify with his work: the concert hall, the audience, the applause?

I believe that the meaning of an homage to Cage, is a tribute to his thought, to the influence he exerted on, but not only, sophisticated music after the 50’s. I second Xenakis’ opinion: Cage’s ideas, his personality, his character, the fracture he provoked; these are the things that will last of him, rather than his music.

3) Please tell us some technical detail about the piece. It is quite an unusual quintet (piano, trumpet, flute, percussions and saxophone) and quite a complex score. Why such an ensemble and what kind of compositional methods you adopted, considering that his a tribute to Cage?

Actually the ensemble is the original Cage Ensemble (Roberto Baccelli-piano, Lucia Barsotti-flute, Riccardo Puccetti-percussions, Giuseppe Angeli-trumpet, Michael Bastianelli-saxophone), hence a ‘given’ collective, very stimulating from a timbral point of view. The whole piece is based on a group of ‘grains’: six fragments of John Cage’s IX sonata from his Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano and ‘variations’ of the afore mentioned Cagean elements. Only the ending element (the sixth ‘grain’) vaguely resembles the original excerpt, to let some original snippets ‘emerge’ from the distorted sonorous magma. The prepared piano has a ‘concerting’ function, as it were.

4) I’d like to ask you a preliminary question before focusing on the bigger picture. If we take Grains and variations as a paradigm, what is it supposed to evoke in the spectator? What sort of emotional or intellectual feelings should it arouse?

It is a complex answer to give. I don’t know what, even a piece like this which is an explicit homage, should really evoke. This stands for the whole act of composing, in my opinion. I believe it would be important to pay attention, to concentrate, to live the experience of listening as an act of curiosity and of sheer pleasure. I know many young fans (people that come from rock, jazz and sometimes also from heavy metal or punk) who, thanks to their curiousness and will of investigation, approached the sophisticated music of the second half of the Twentieth Century and later contemporary music too, and without any knowledge of their compositional praxis or the formal analysis of music, deeply enjoy them. My answer to “what is evoked in the listener” is therefore always the same one: a deep pleasure. Even when we move from more accessible experiences like the American minimal music to more difficult works like those of the ‘new complexity’, just to mention two groups.

5) What is contemporary music today? Which guides or developments can be considered research and modernity? But above all, who is contemporary music speaking to? What is its political and social content in relation to the language it uses, often demanding for the majority of the people?

What is contemporary music… how can I answer this? Many composers (especially young ones), often really interesting and each one endowed with a sonorous richness and stunning ideas, from work to work. It’s hard today, due to the speed and the combination of suggestions and deep cultural com-penetrations (I’m thinking of the insertion of extra-European instruments into a sophisticated Western musical language, or the interaction among instruments/ensemble/orchestra and live electronics, for example), to trace a defined borderline around contemporary music. This sea of sound is addressed to who has ears and passion; an audience sometimes younger than we could imagine and that thanks to the web arrives to the promotion of concerts, panels and meetings from the bottom; let’s think of the potential of a channel like YouTube for instance. It allows the spread in a good audio/video quality of full or excerpts of concerts of interesting composers, musicians and ensembles, who would remain unknown otherwise. Fans and listeners increase consequently and the dogma of a public formed only by musicians, composers and artists is finally violated. However, I think that is urgent (more than Luigi Nono’s experiments in the 60’s and those of Pestalozza, Giacomo Manzoni, etc, or the fundamental experience of Musica Realtà in the 70’s) to bring music out of the concert halls, today more than ever, in search of (and to invent!) new places for listening and so new opportunities to meet who is not used to the experience of contemporary music.

6) Two more aspects come into play now. Maybe they could complete the discussion upon the listener/fruiter of sophisticated music: the coherence and the responsibility (the latter both of the spectator and of the composer). Moreover, it must be taken into account the fact that the audience has changed in the last century. Perhaps the social evolution was not as fast as the musical one. What do you think about this?

Well, surely if we think about the mechanical reproduction of music first and about the access – with a little bit of patience and a computer – to an unlimited universe of music genres secondly, we must realize the difference and the new rapport with fruition in the listeners compared to those of just twenty years ago. The problem remains the same: a balance between attention and ‘investment’ of time for searching, studying and eventually listening to a certain kind of music. To find one’s way within this ocean of music randomly, hoping to stumble upon some good one, is purely Utopian. We need to inform ourselves, sort through and finally focus on in order to fully appreciate our choice. Who is not interested and does not want to try to confront with the investment of one’s own time, well… stay home!

7) It is commonly said that contemporary music is also avantgarde music: does it make sense to talk of musical avantgarde today?

I wouldn’t use this term nowadays, as it is tied to another era. How and where musical avantgarde can be detected? The work of an Armenian or Russian composer could be as avantgarde as that of a New-yorker one, even if they come from very different musical paths and use diverse compositional and structural elements.

8) Isn’t it true that contemporary music has its own ‘code’ – more complex compared to the traditional classical music – yet already recognizable?

There are contemporary pieces that are ‘coded’ (to use your own term) in ways that look like some bad music from the Nineteenth Century, others that hint at improvised music, others that immediately lead you to (despite they are played with traditional instruments) electronic music. The experience of a composer sometimes is so elaborate – due to the overlapping layers of work, research method, analysis, will to explore which fosters his own stimuli and urgency through new structural forms, new points of arrival – that it’s already hard to ‘code the composer’ within two pieces of the same author (to accomplish too quick a necessity to classify a determined compositional school). Not to mention the concept of ‘genre’ ascribable to the cliche of dissonance.

9) The greatest fracture with the past was due to Schönberg: dodecaphony and atonality. Is it reasonable to think of a return to tonality?

Honestly, since the beginning in the Conservatorio, I had never thought of dodecaphony as a fracture, rather as a consequence of the path of Schönberg and his famous pupils (in the known utilized forms), but not only. In the same way, the praxis of harmony of a certain time has always felt the need to open itself, to evolve, to include new exceptions that would later become academic and so forth. That said, if you mean a return to compositional ideas based on ‘canonical’ forms that re-write the past (and I would personally include dodecaphony and serialism in this category also), yes, there are many, but I am not into them.

10) Could you indicate some living composer, who is particularly interesting for the development of contemporary music?

Actually there are many composers (a lot are Italian) that I like and it’s great to have the chance to live such a flourishing phase rich of differences and peculiarities. Among the Italians (only to cite a bunch of them and without recalling the already famous ones): Marco Marinoni, Maura Capuzzo, Andrea Nicoli, Marco Alunno and most of all Riccardo Dapelo, composer from Genova, a very wit mind who has been my first reference as a teacher. The panorama is so vast (even in such hard times) and varied, that it’s difficult to list just few names.

**********************

Short biography

Lascia un commento